In the afternoon of September 5th, we finally reached Peninsula Valdés. It’s not a national park but a ÜNESCO World Heritage site. It is one of the most important marine reserves in South America, offering a critical breeding ground for southern right whales, as well as a habitat for Magellanic penguins and elephant seals.

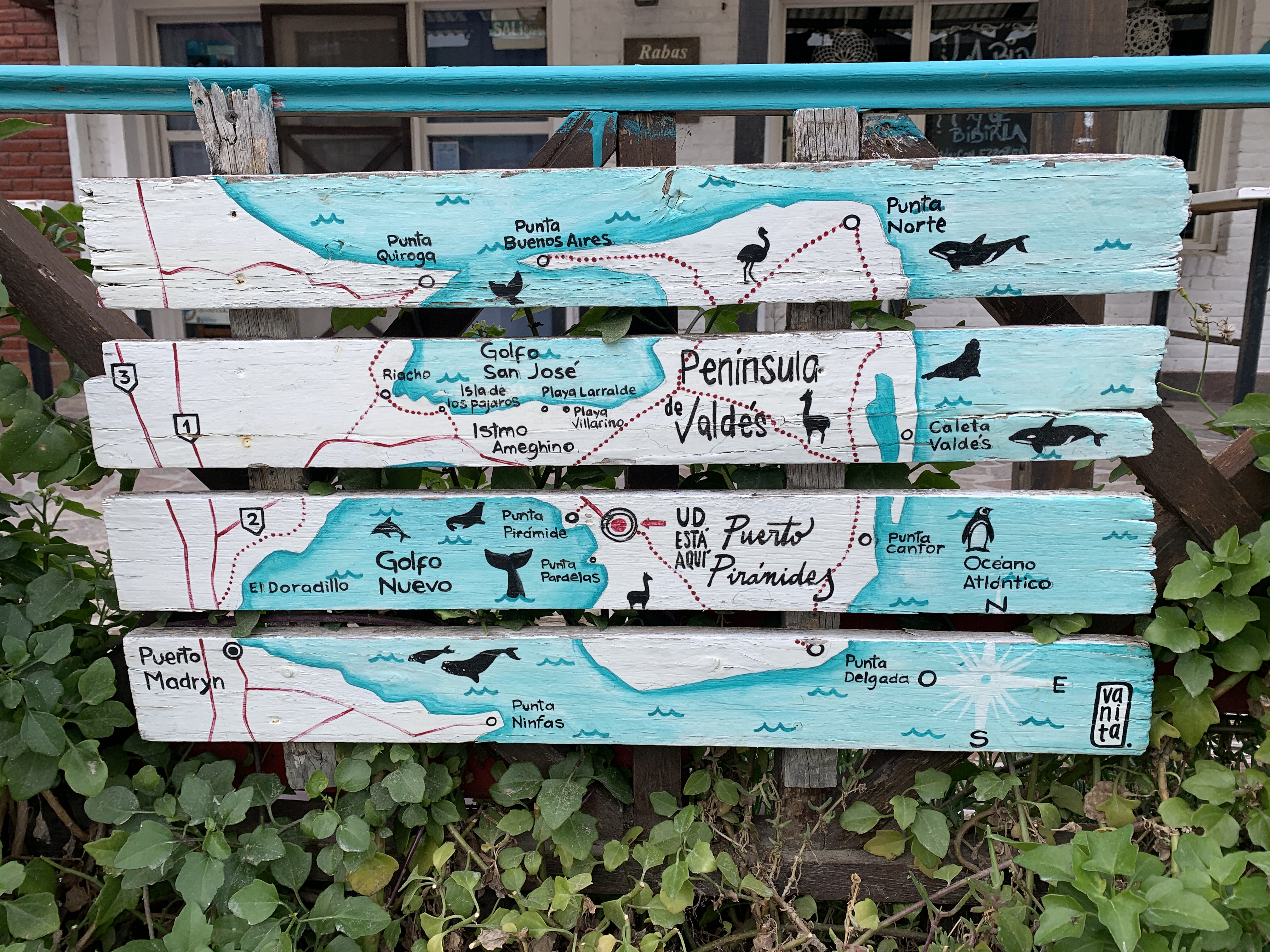

Mönths ago, this was the first thing I read in the Lonely Planet South America before bed in Berlin and told Björn, we have to go there. On the map, the peninsula looks fairly manageable. However, it was quite a drive from Ruta 3, about 85 km to the town of Puerto Pirámides in the province of Chubut. Before that, we passed the park entrance and the visitor center, providing a bit of variety along the way. As “foreigners,” we paid 30,000 Argentine pesos per person for entry. By comparison, Argentinians pay 10,000 ARS and residents of the area pay 5,000 ARS. We thought it was quite expensive, but we were determined to go. At the entrance, we learned that the campsite in Puerto Pirámides was officially closed, but we could still park there, something we had already researched via Internet and iOverlander. Camping elsewhere was prohibited. Along the roadside, we were greeted by a herd of curious guanacos (llamas), which would accompany us for the next few days and thousands of kilometers.

At the visitor center, they told us which roads were closed, what was recommended in this season, and which animals we could see. We were excited. Puerto Pirámides, with a population of about 500 people, is the only inhabited place on the peninsula and offers accommodations, restaurants, and tourist services. And since we were running out of gas, a YPF gas station. Yes! Upon arriving, we drove to the campsite and joined five other vehicles: a large converted bus, a rented Argentine caravan, and two pickups with camper shells, one from Brazil and one from Argentina. We all parked far apart. Behind the bushes was the beach, and we took a walk in about 15°C weather with clouds. We strolled along the beach and watched the whale-watching boats return, being pulled from the water onto the shore by a tractor with a special rig, unloading a crowd of orange life jacket-wearing tourists.

We continued to “small mountains” on the coast and in the heart of the town. These are walkable sedimentary hills made of hard, compacted rock. The formations are the result of thousands of years of sediment deposits, shaped by erosion, leaving rugged surfaces. Walking over these ancient layers of shells, you can clearly see the distinct layers. Some even contain old caves that people used to build into the sedimentary hills. Once we reached the top, we spotted whales in the ocean. It was a magical moment to see whales so close from the shore. While we’ve both seen whales from a boat before, this was extraordinary. Unfortunately, we also came across a dead whale on the beach, with seagulls picking at it. On the way back, we visited the tourist office to learn more about the whale species we were observing — they were southern right whales.

We quickly realized we needed to grab the camera, as the sun was coming out. The gray sky turned bright blue, and we spent more time watching the whales from the shore. A few young sea lions also came close to the beach to play. We ended the evening in a small bar with a sea view, enjoying Patagonia beer and Kölsch on tap while watching the whales. Björn’s note: I want to repeat this. You sit at the bar with freshly tapped beer, the sun is shining, you’re looking at the sea, and you’re constantly seeing whales. How amazing is that?

The next morning, under clear skies and beautiful morning light, we were already on the road by 8 AM, heading to the viewpoint at the easternmost point of the peninsula. However, the road, as we knew it, quickly turned into a 15-meter-wide sand and gravel track. The speed limit was 60 km/h, ha ha ha. We rarely reached that. While Rosi can handle a lot, this was her limit. The ultimate challenge: the “washboard” road. This phenomenon occurs frequently on unpaved roads, formed by repeated vehicle movements that cause the loose gravel to compact into wave-like patterns. It can be so severe that you have to drive at walking speed or stay on the edge through the sloping sand. We’re talking about 80 km of this, and then back again, since the loop road was closed.

Along the way, we enjoyed watching guanacos and birds. We were shaken quite a bit and feared rock damage whenever someone passed us. For smaller cars, the washboard road seemed less of a problem. At the point, we saw the stunning coastline, which looked different each time we visited. Here, the coast was relatively flat with pebble beaches. In the distance, we saw small hills and tire tracks that we couldn’t quite identify. They looked like rocks. At the viewpoint, an info board told us that orcas had been spotted the day before. Unfortunately, we didn’t see any that day. However, we could now view the small hills up close and realized what they were — elephant seals. Tired, sleepy elephant seals barely moving. They were lying about 15-50 meters apart, sunbathing at the water’s edge. The tire tracks turned out to be made by the elephant seals themselves. No wonder these huge animals sleep so much. In the water, they are much more active.

Elephant seals spend most of their lives at sea and return to land only to breed and molt. Male elephant seals can spend up to 8 to 10 months a year in the open ocean, while females spend about 7 to 9 months. During this time, they travel enormous distances, often covering several thousand kilometers, and can venture as far as 2,000 kilometers from the coast of Peninsula Valdés in search of food in the deep waters of the South Atlantic. During the mating season, dominant males control harems of 40 to 100 females. These males aggressively defend their harems against rival bulls to ensure they can mate with as many females as possible. However, we didn’t observe this behavior. They were simply lying and sleeping peacefully.

We took a short hike through the dunes and thought we spotted penguins in the distance. It turned out to be black-and-white cormorants. We also saw a few small rheas and Patagonian hares. On the way back, we spotted a bull elephant seal with his distinctive nose on the beach. Nearly back at the campsite, we visited a lobería (sea lion colony), where we spent some time watching whales and countless sea lions. The weather was perfect, and we enjoyed the sunshine and the wonderful view of the sea. On the way back, we picked up a German couple who lived in Lüneburg and were moving to Potsdam. The husband was Argentine, visiting his family, and they were grateful for the ride as they had to catch their long-distance bus.

That evening, we could hardly believe our luck. We had already seen a notice that the showers on the closed campsite would be open from Friday to Sunday between 6-8 PM. We braced ourselves for cold showers, but to our delight, there was hot water — although only in the men’s shower. We happily waited our turn, and after three women finished showering, we were finally able to get in. It was properly hot and felt amazing.

After a cool night, we got up early, dumped our gray water, and filled our tank with drinkable fresh water. Yes! To sum it up: Two nights at a campsite in a nature reserve right by the beach, hot showers, trash bins, fresh water, and waste disposal — all for free. We were very satisfied and left Valdés with a vacation feeling. But we made one last detour down a closed gravel road (meaning we definitely had to come back the same way) to the Golfo Nuevo. There, we had breakfast and watched the whales from the shore again. We couldn’t get enough. You can even hear them exhale when they blow water, and you forget everything around you. Especially the strong wind, which was expected to get even stronger in the coming days. Back to Ruta 3. We want to see penguins.

Leave a reply to dutifullyshinyfc78a73c84 Cancel reply