Heading to Uyuni, yes. We were so excited and full of anticipation, finally, a normal road! What would it feel like to drive on it? First, we poured the remaining diesel from our jerry can into the tank and admired Rosi. Her color was no longer visible. She was completely coated, like a breaded schnitzel, but with fine dust and sand. Really dirty. It was already past noon, and we had 150km of Ruta 701 ahead of us to reach Uyuni. In Germany, that distance is covered quickly, but here everything takes a bit longer. We knew we wouldn’t make it to Uyuni that day, but no matter, we just wanted to keep going. We were excited. Reality soon caught up with us. The road wasn’t much better than parts of the Lagoon Route. To be precise, it had every kind of surface you could imagine: deep potholes, loose gravel, compacted clay and sand, dusty tracks and fine sand… The worst part was driving most of the time alongside a brand-new, perfectly asphalted road. Unfortunately, it wasn’t open to traffic yet. Ruta 701 is one of the main connections to Chile, so there were many trucks on this road. On the sandy sections, when oncoming cars stirred up dust, visibility was reduced to zero, like driving through fog. Okay, the road wasn’t quite as bad as the Lagoon Route, but it was bad enough when you had been looking forward to a good road. The Lagoon Route didn’t just stick to Rosi’s coating. Sand was in every crack and hinge, and even came through the air vents. A lot of sand. Note to self: change the air filter in the next few days. In San Cristobal, we stopped at a gas station and witnessed, for the first time, a pump roped off and empty. We were told there wouldn’t be more diesel until the next afternoon. At least we could refill our nearly empty drinking water reserves (we drank a lot at this altitude) and inflate our tires to the proper pressure (back up to 3.5 bar from 2.2 bar) at the garage next door for 4 Bolivianos (50 cents). Our air compressor seems not to work at high altitudes, or maybe it’s just broken in general.

We bought a few things in town, no prices were displayed, and I think the seller ripped us off because it was really expensive. The pack of spaghetti was taped shut, but I only noticed when we were back in the van and the pack burst open and the noodles spilled out. I also managed to activate the SIM card I swapped with Lisa in San Pedro de Atacama, which I had already uploaded online. It worked! Suddenly, we had network access and contact with the outside world again. As evening approached, we found a place to sleep in Vila Vila near the local soccer field and cemetery. Using our outdoor shower, I tried to remove the worst dirt from the hinges and handles. The next day, Rosi looked even worse, spotted and dirty. But at least the handles and door frames felt cleaner.

Train graveyards and diesel shortage

We continued to Uyuni, located 3670 meters above sea level. To us, it felt like being at sea level again, we barely noticed the altitude anymore. We had read beforehand that entering the salt flats with your vehicle during the day could be problematic, so we decided to try in the afternoon. First, we visited the Cementerio de Trenes In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Uyuni was an important railway hub, mainly transporting silver and other minerals from nearby mines. With the mining industry’s decline in the 1940s, the trains were decommissioned and left behind. Today, the rusting trains resemble art pieces. Some locomotives have been adorned with graffiti, while others are slowly disintegrating in the harsh environment. After taking a few photos and finding a geocache, we headed into Uyuni itself.

The town, laid out in a grid, was dusty and full of tourists. At Llama Café, we enjoyed delicious coffee and a quick lunch. Finally, we restocked on fresh fruits and vegetables at the local market after a week without. I love markets, and here everything was incredibly cheap and fresh. The people were friendly and honest about the prices. Next came the most important task: diesel. At the gas stations, there were kilometer-long queues of waiting vehicles. We heard from other travelers that foreigners should approach the attendant with a jerry can, ideally, as a woman, and politely ask. That’s what I did. I felt awkward walking past all the waiting cars and trucks, but at the pump, things moved quickly. I asked in Spanish for 20 liters of diesel, explaining I needed it to leave the country and didn’t require a receipt. The attendant gave me a price, slightly higher than usual but still cheap compared to other South American countries (8 Bolivianos per liter, about €1) After fueling a truck and another jerry can, he filled mine. I was so relieved, we would make it back to Chile for sure. Later, we learned that some tour guides or truck drivers have to wait up to three days for fuel, unable to work during that time. Despite my success, I still felt a bit awkward about the situation.

Sält as far as the eye can see

With the diesel, we made our way to the Salar de Uyuni, the world’s largest salt flat, covering about 10 582 km2. Formed around 40 000 years ago from the prehistoric Lake Minchin, which dried up and left behind a thick salt crust, the surface can be up to 10 meters thick in places and conceals brine rich in lithium and other minerals. During the dry season, the salt flat displays geometric patterns on its white crust. In the rainy season, water covers the surface, transforming it into a giant mirror. We arrived just before the rainy season began in December, so we could still drive on the dry crust. We read about people whose campers broke through the surface. There are also areas to avoid. Initially, we considered entering from the south, which was closer, but many vehicles reportedly get stuck on that route, so we took the longer way around. On the salt flat, we stuck to the established routes. With our limited diesel, we didn’t drive too far in. The Salar is about 100 km wide and 135 km long, you could easily get lost or run out of fuel. We explored the highlights: the Dakar Monument, the Hotel de Sal, and the Plaza de las Banderas. The Dakar Rally passed through the Salar de Uyuni several times, especially from 2014 to 2018. It became one of the most spectacular stages of the rally as the vast white expanse and extreme conditions posed a unique challenge for drivers and teams.

We set up camp at the Escalera al Cielo, the Stairway to Heaven. The next day, we planned to take perspective photos around noon, as the sun would be at its highest, and people and objects would cast no shadows. During the photoshoot, we were visited by Jule and Michi. They’ve been traveling just like us since August and came from the north, like most of the travelers we meet. We parked both vans (they drive an old VW T4 with a pop-up tent) and set up a tarp between the cars to create some shade. It was windy and cool, but the sun, reflected off the salt, was even stronger than usual at this altitude. Guess what happened? That’s right, I got a nasty sunburn on my face because I sat just a little outside of the shadow and took off my hat. Even though I wore sunscreen. We spent the day together, exchanged information about the roads north and south, and cooked together in the evening at the train graveyard. It was nice to have company. Our original plan was to take the bad road back toward the Lagoon Route due to the diesel situation and roadblocks in the country and cross into Chile there. We intended to drive north along the Chilean coast and possibly head to La Paz afterward. Jule and Michi told us how great the road was from here north toward La Paz. Plans, as we know, are meant to be broken. And that’s what we did.

Austrian Lifts, Witches, Shamans and Lama Fetuses

The next day, we headed north toward La Paz, crossing Bolivia. There were no roadblocks on this route; they were more common in the west of the country. But first, we went to the market together, filled up the diesel cans again (this time Björn had to go, and it worked again!!!), and said goodbye to the couple, who were now heading for the Lagoon Route. Thanks again to Michi, who gave me a sensor cleaning kit for our camera after all the dust and sand. Rosi got a very thorough car wash, which cost around €9 and took over half an hour. Several kilograms of sand came out from under Rosi’s underbody cover. And fist-sized stones (children’s fists). It’s important to clean the car after driving through the salt desert. Not that Rosi didn’t need it anyway. Afterward, she sparkled, and nothing was broken. Yay! Often parts break because the car washers gets a little too enthusiastic with the pressure washer, getting too close to sensitive parts.

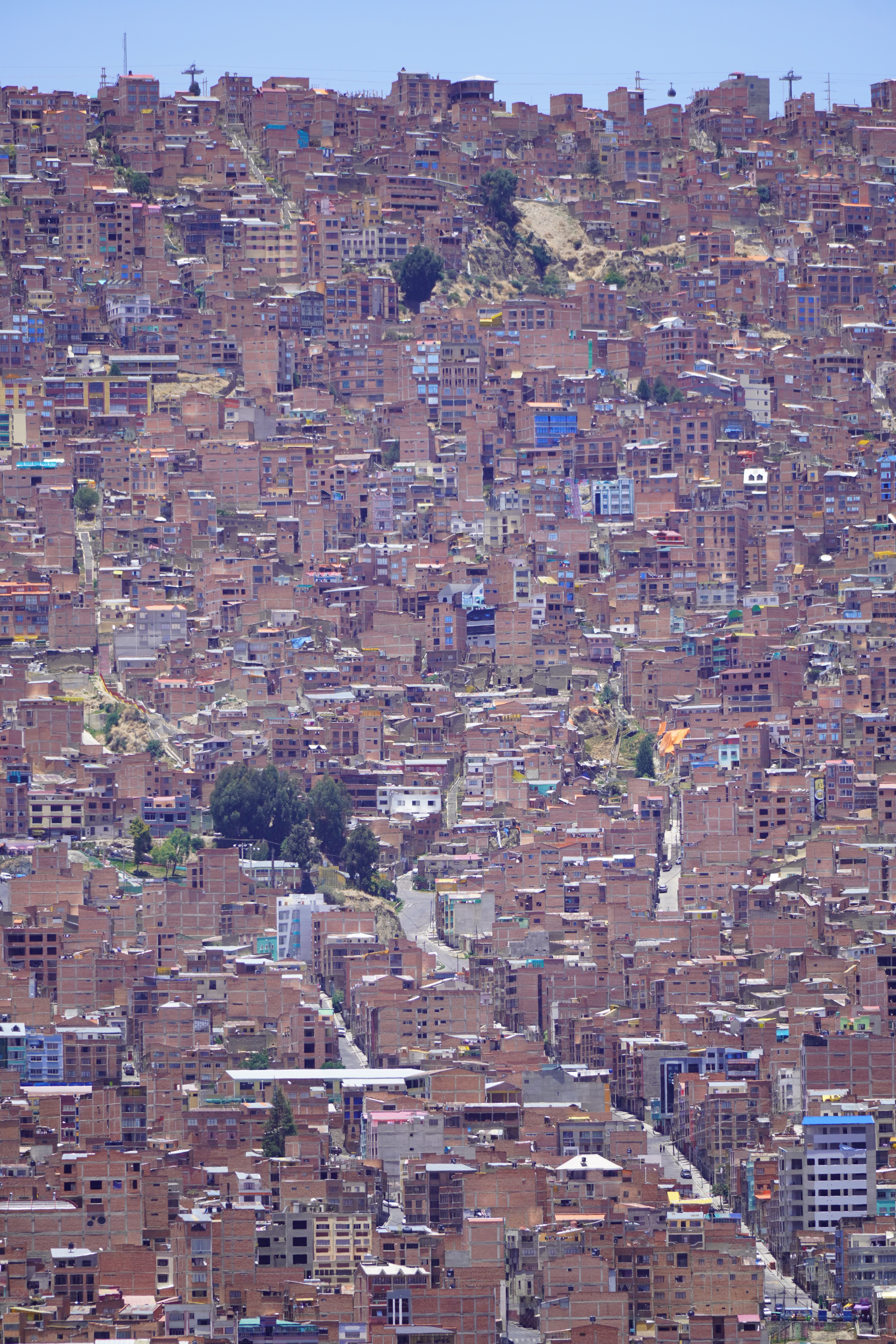

On the way to La Paz, we saw the real Bolivia, without tourists or tour jeeps. Simple, small houses. Tied-up cows, sheep, and pigs by the roadside. Traditionally dressed Bolivians. We also saw the first tuk-tuks. Small mopeds with a cabin that can fit three people. They look like tiny cars, mostly in Batman design. It took us two days from Uyuni to La Paz, with an overnight stop near the dried-up Lago Poopó. Unfortunately, we had to go through the big city of Oruro, which took us some time and nerves. The arrival in La Paz was just as challenging. Google Maps directed us down a steep gravel slope. For those who, like us, had never been to La Paz, it’s hard to imagine what it’s like to drive there. It is very steep. Cars honk and cut in front of you. You don’t feel very comfortable on the road. The city lies in a bowl, surrounded by tall mountains: Illimani (6438m), Huayna Potosí (6088m), and the now-vanished Chacaltaya ski resort (5421m). The city extends at an altitude of about 3200m in the lower, wealthier zones and up to over 4000m in the higher, poorer neighborhoods like El Alto, which is not a district of La Paz, but a separate city. The altitude difference is over 800 meters. Together, the two cities form Bolivia’s most populous urban area, with 1.8 million people.

By the way, La Paz isn’t really Bolivia’s capital; that’s Sucre. It’s not accessible to us, as there are roadblocks there. However, La Paz is the government capital, housing the presidential palace and the parliament. So, we drove along a gravel road into the bowl, through the beautiful Valle de la Luna, a moonlike landscape with pointed formations of clay. On the other side of the city, we had to climb a steep road up to the campsite. Jule and Michi had recommended it to us. There were hot showers, a self-service washing machine (a very rare find, which we used twice), a sitting area, and an amazing view of the city. It was more of a car workshop with a small camper area, but nice. For two days, we were the only ones until an older French couple with their off-road van joined us. We didn’t speak French, and they didn’t speak English or Spanish, so our conversations were limited to “Alors, buenos dias, merci, oui, si, au revoir.” Björn and I were always amazed at how many older people travel the Pan-American Highway. They were probably in their 70s. On our first day in La Paz, we did an 8-hour city tour with Gerd. It wasn’t easy to get to the meeting point of the Teleférico, but thanks to Uber, after 30 minutes of waiting, we got there for about €2. All of La Paz is crisscrossed by cable cars from the company Dopplmayer (exactly like ski lifts in the Alps and just as modern), which locals can use to get around, instead of taking the minibus or mototaxi or tuktuk like most of them do. Gerd was born in Germany, and his family moved to South America early; he’s been living in La Paz for 40 years. We learned a lot about Bolivia’s history, government, and the country’s issues. From the Mirador Killi Killi, we had an incredible view of the city. We explored the government district, ate Salteñas (similar to empanadas but with firmer dough and a liquid filling – the trick is not to spill any), and visited the Sunday market in El Alto. The market in El Alto is one of the largest in South America, and perhaps even the world. It spans several square kilometers and runs through many streets of the city. The market is so large that it takes hours or even a whole day to explore fully. Here, you can find anything, really anything. In El Alto, we marveled at the Cholitas and their fashion, and the Cholets. Cholets are an iconic architectural phenomenon in El Alto. The term comes from “Cholo” (a term often used to describe the indigenous population) and “Chalet.” These extravagant buildings are a symbol of the growing wealth of the indigenous Aymara elite and blend tradition with modernity. The best place to view them was from the lift.

Finally, we went to the Witch Market, which is much bigger than the one in La Paz. From there, you get a great view over the city and the surrounding mountains. We saw witches and shamans performing rituals and visited the shops where they buy ritual items like dried flowers, sweets, alcohol, coca leaves, roots, and even llama fetuses (we also saw piglets). Many Bolivians believe in this and visit a shaman, for example, before an important event or to cast a spell or protect themselves. It’s an important part of the culture. A Yatiri (shaman) performs the ceremony, where the offerings are burned or buried in the earth.

Llama fetuses play a central role here, especially among the Aymara and Quechua communities. They are important offerings for Pachamama (Mother Earth), who is worshiped as a divine protector and giver of life. The fetuses are used as offerings to thank Pachamama for gifts like good harvests, health, and prosperity. It’s believed that the sacrifice strengthens the connection between humans and nature. The fetuses are often buried during construction projects, like building a house, to appease Pachamama and protect the project from misfortune and disaster. The fetuses generally come from natural miscarriages. Given the number of fetuses we saw that day, I don’t believe this is always the case.

Although I love cooking in Rosi or finally grilling with Skotty, when we’re in cities, we really enjoy eating out. So after the long city tour with Gerd, we found a ramen restaurant that made us very happy. A perfect day.

Badass-Cycling in Bolivia

The next day, we booked a mountain bike tour over the Death Road. The Death Road (officially Yungas Road) is often called one of the most dangerous roads in the world. It was built in the 1930s by Paraguayan prisoners of war during the Chaco War. Due to the high number of fatal accidents, it got its name. Since the opening of a new, safer bypass road in 2006, the Death Road is hardly used by cars anymore. Currently, it can’t be fully traversed because a stone ledge recently slid onto the road and blocked it halfway. We booked with the highest-rated tour company, Gravity, because our safety was a priority. The next day, we woke up at 5 a.m., took an Uber into the city, and had breakfast with the group in La Paz. After breakfast, we drove for about an hour by minibus to the start of our tour. We started in the fog at 4650m at the snow-capped La Cumbre Pass, then rode downhill for 64 km, eventually reaching the tropical jungle at 1200m after several hours. Initially, we rode on paved roads before hitting the official Death Road. From there on, it required full concentration. Still, I preferred to ride at the front behind our guide since you could go the fastest there. It was amazing to admire the landscape, feel the wind in my hair, cross small rivers, and ride under waterfalls. It was an incredibly fun experience, which ended after several hours in the humid jungle with an altitude difference of almost 3500m. At the destination, we had spaghetti Bolognese, a cold beer, and the “I survived the Death Road T-shirt”. What an awesome experience. Even if the road had been passable by car, we wouldn’t have wanted to drive Rosi there. It’s a gravel road with a very narrow, uneven surface, often only 3 meters wide. On the route, vehicles must drive on the left, meaning you’re always on the edge, and the steep cliffs of up to 600 meters often have no guardrails. Also, fog, rain, and landslides make the road slippery and dangerous. Plus, there’s hardly any room to pass if you encounter traffic.

At the campsite, we took care of a few things before leaving, such as replacing the air filter. Finally, no more dust from the Lagoon Route was coming into the driver’s cabin. After five days, we left this crazy city, which we had come to love. We hadn’t planned to go here at all. At least not directly. And we hadn’t wanted to visit big cities on our trip, fearing break-ins. But we had a great time here. Bolivia, you challenge one, push one to the limit, offer beautiful nature, and have strongly impressed us. So far, my highlight of the trip.

Leave a comment